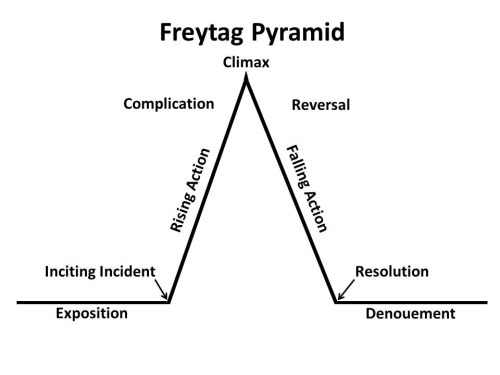

The book club has a history of reading strange and unsatisfying books by Japanese authors, (wow that sound terrible... I don't mean that all books by Japanese authors are terrible! They just happen to choose not so great ones...) which is one of the reasons I haven't gone since the first time I went after reading Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami. So, I'm actually really surprised that members were still shocked and annoyed by the lack of a traditional resolution seen in Western stories. The thing is, Japanese stories don't usually follow the Western tradition that has a beginning, climax, and resolution...you know, that triangle.

Here's that triangle for clarification:

So yeah, this is a Western concept, and it's what we've come to expect as Western readers, and so it's always interesting when there are deviations and plot twists. Our stories thrive because they are conflict-driven and, thus, require a resolution for us to really feel like the story ends. However, Japanese authors do not generally follow this typical narrative setup in modern literature.

If you watch a bunch of anime or read a bunch of manga, you may have even noticed the common concept of just exposing the audience to a piece of someone's life.

If the story or person's life is this long [-----------------],

then you get this much [----] of it when the author writes the story.

You start on a regular day for the main character and end on a regular day usually. Things happen to the protagonist, who is generally bland (and what I mean, is that they don't usually have any super strong defining character traits, and they usually don't stand out too much compared to other characters). And the protagonist doesn't generally go looking for trouble, per say. There isn't a conflict present to start and be solved to end the story. I think stories are set up this way to help the audience be able to project themselves onto the protagonist and imagine themselves in the story and identify with the main character. If anything, they have one life moral driving their actions like friendship or protecting loved ones or trying to be the best at whatever they do, which are pretty general and relatable. You could look at almost any JRPG video game's protagonist or slice of life manga or anime for some good examples (like Persona 3, Final Fantasy VIII, Inuyasha, One Piece, Fruits Basket, Ouran High School Host Club).

So yeah, Japanese story telling in modern manga and anime and literature is more of a ride, an experience you get to peek into. There can be rising and falling action and and conflicts and climaxes and resolutions, but they're just not required for the plot. You can definitely still get invested in the story and characters just like a Western-style story, but the ride is just a little different.

Here are some linkies for more on Japanese narrative if you're interested on reading more about it.

Wikipedia on Japanese narrative structure (Kishoutenketsu)

An essay about lack of conflict with comic illustration examples

No comments:

Post a Comment